Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and (currently) a PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. Just as his most recent book (Tous Malades !: Quand l’obsession pour la santé nous rend fous) was being published, I met Pierre on Twitter, where we discovered our mutual interest in the subject of healthism. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and (currently) a PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. Just as his most recent book (Tous Malades !: Quand l’obsession pour la santé nous rend fous) was being published, I met Pierre on Twitter, where we discovered our mutual interest in the subject of healthism. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

This translation would have been impossible without the invaluable assistance of Jan Henderson (PhD in the history of science and medicine from Yale). Her work allowed me to revisit the original French text and enhance it, and in this sense, we followed the injunction of Karl Popper : the duty of clarity. I hope our collaboration will continue, because Jan and I are particularly concerned about the healthization of society, and we try to understand how health has become a social value. Feel free to send us your comments (Jan Henderson, Pierre Fraser).

Pierre Fraser, 2012

When a medical clinician examines a patient, she first determines the presenting symptoms, considers which bodily functions might account for those symptoms, arrives at a diagnosis, and provides the most appropriate treatment. But what if the presenting symptom is depression? As Alain Ehrenberg points out, “depression, like any mental illness, is not a disease that can be assigned to a part of the body.” [1] In fact, as Ehrenberg goes on to say: “when psychiatry can discover the cause of a mental illness, as happened with epilepsy, it is no longer a mental illness.” [2] Such has been the dilemma of the history of psychiatry.

Consider, though, what has happened in the history of depression. Seventy years ago an individual who suffered from depression was considered sick, but curable. Today our assessment is that such an individual has a chronic disease. [3] How can we explain this historical progression?

When we look closely at the history of psychiatry it teaches us one thing very well: “disagreements about the causes, definitions and treatment of diseases, as well as the uncertainties that have accompanied the history of psychiatric reasoning, are particularly revealing about the transformation of the individual.” [4] Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, our concept of the individual has undergone fundamental transformations. Given that we now hold “the gospel of personal development in one hand and the cult of performance in the other” [5], we can see that “the history of depression reveals how the type of person we have become has followed in the wake of demands for psychic emancipation and individual initiative. What insanity is to reason and neurosis is to conflict, depression is to insufficiency.” [6] Emancipation and empowerment bring the expectation that the individual will perform. But will that performance be adequate? Depression is the result of feeling that our life’s performance is not sufficient.

A social bond in crisis

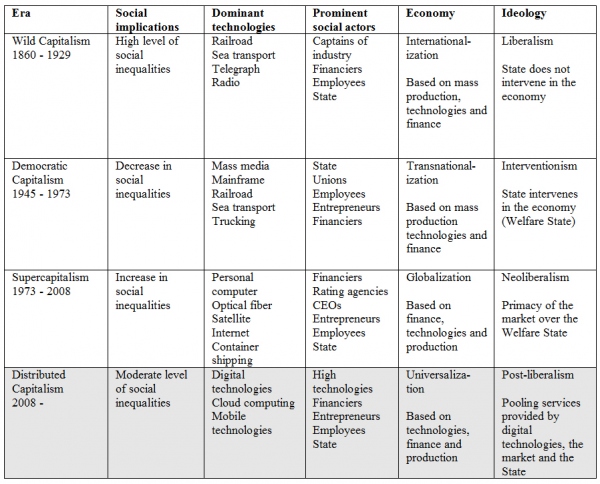

The Age of Wild Capitalism (1860-1929) was dominated by the captains of industry. Private enterprise reigned supreme and regard for the individual was at the same level as regard for commercial merchandise. This was followed by the Age of Democratic Capitalism (1930-1973), when the state, in response to the Great Depression, began to intervene in markets by imposing regulations. The Age of Supercapitalism (1973-2005) began with the first oil crisis. The economic difficulties of the era created an opportunity for President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to deregulate a variety of economic sectors. The period culminated with globalization. Finally, I would like to propose that we are now in an Age of Distributed Capitalism [9] where the dominant influence will be high-tech industries. This stage will enable the complete empowerment of individuals: they will be fully in charge of their lives through the use of inexpensive and widely available technologies.

In this table what stands out first and foremost is a correlation between the dominant ideology of each era and the relative hierarchy of the players. In the Age of Democratic Capitalism, the state is the most prominent social actor. Entrepreneurs and financiers are relegated to the bottom of the scale. This is a complete reversal of the positions they held in the previous age. The reversal is apparent not only in the rise of unions, but in the implementation of major social protection programs that are characteristic of this age. Though these programs took on different forms in different countries, the intention was the same. We see here an example of what Durkheim called ‘organic solidarity’: a social cohesiveness and interdependence that arises from the division of labor. This state of affairs allows individuals to benefit from the basic protections of society while feeling their contributions are valued as useful. [10]

On the grammar of depression

The Age of Democratic Capitalism appears, at first glance, to be highly favorable for the individual. Thanks to various social measures, it was a time when the state offered increased protections against life’s misfortunes. Living conditions improved for all economic classes. Purchasing power increased annually, and “those born after 1945 not only have the best physical health in modern history, but have also been raised in a period of unprecedented prosperity.” [11]

It might seem paradoxical that the prevalence of depression would increase in this era, but this was definitely the case. In 1989, the American Medical Association published a summary of epidemiological studies of depression and concluded: “the increased risk of depression for those born after the Second World War is indisputable.” [12] There had been an astonishing amount of material progress, yes, but this was accompanied by “urbanization, geographic mobility, emotional breakdowns, the growth of social anomie, changes in family structures, and the embrittlement of gender roles.” What is especially interesting about the epidemiological studies is that they all converge on the same explanation for the rise of depression: social change.

We must admit that social change alone cannot explain everything about depression. There must also be a ‘grammar of depression’ through which individuals may conduct their own diagnoses, and this grammar can only exist if depression is institutionalized. Around 1960 “anxiety, insomnia and overwork as the themes of depression appear publically in major magazines.” [13] They provide “an interpretive tool to solve or overcome intimate problems.” [14] In other words, depression involves actors who supply the hows and whys of their problems, while mass media tell people how to deal with those problems. Depression is thus “produced in a collective construction that provides it with a social framework in which it exists.” [15] Depression becomes a social reality and a “grammar of the inner life for everyone.” [16] Once individuals understand that they are subject to depression, however, there is a social crisis. If individuals regard themselves as depressed, will they be able to perform the roles expected of them by society? A society functions best when its members feel that what they are doing is useful. Depression, with its sense of the insufficiency of the individual, calls this into question. A society needs motivated, mentally healthy citizens, but will it be able to alleviate the widespread incidence of depression?

As Alain Ehrenberg has emphasized, “democratic modernity — this is its power — has gradually turned us into men who have nothing other than our own selves to guide us. We are gradually put into a position where we have to make our own judgments and create our own standards.” [17] The possibility of living our lives as sovereign, autonomous individuals has not only become a reality for some of us, as anticipated by Nietzsche, but is now the common reality for everyone. In times past, an individual who did not respect the rules (what is permitted/prohibited) was seen as guilty of a ‘sin.’ Today, however, he is blamed for a ‘failure of responsibility’ (what is ‘possible/impossible’). The individual can no longer agree to accept the label ‘guilty’ without giving it much thought. The sovereign individual must feel the weight of responsibility for his actions. This reconfiguration of the individual self brings us back to the contemporary prevalence of depression. As Ehrenberg points out, depression is now something intrinsic to the individual: “it is the failure of internal resources.” [18]

About depression

It is quite possible that depression is an anomic condition (Durkheim). That is, it occurs in contexts where the individual, confronted with the duality “possible/impossible,” feels he must “be himself,” but he lacks the “instructions” for how to accomplish this. We are no longer expected to conform to an obvious discipline. We are required to “be ourselves.” Depression, as Durkheim suggests in connection with suicide, arises from the “malady of infinite aspiration,” where everything seems possible, but in fact, nothing is possible.

To answer the basic question with which I began — whether there is a causal link between depression and the increasing empowerment of the individual — it seems plausible to say yes, given that “projects, motivation, and communication are now norms that dominate our culture.” [19] “Depression becomes, so to speak, how the individual safeguards himself. It acts as a kind of counterpart to all the energy that must be exerted simply to maintain the self as sovereign.” [20]

© Pierre Fraser & Jan Henderson, 2012

[1] Ehrenberg Alain, La fatigue d’être soi, dépression et société, Odile Jacob (poches), Paris, 2000, p. 21.

[2] Idem, p. 22.

[3] Idem, p. 251.

[4] Idem, p. 22.

[5] Idem, p. 255.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] I designed this table in 2009 — to gain an overview of the historical eras — when I co-authored the book “Les imbéciles ont pris le pouvoir, ils iront jusqu’au bout !” Published by “Near Future.”

[8] Krugman Paul, L’Amérique que nous voulons, Flammarion, Paris, 2008, p. 352.

[9] This is currently a speculative proposition that must be supported by empirical evidence from current trends.

[10] Durkheim Émile, De la division du travail social, eBooksLib on iBookStore, iPad version, p. 377.

[11] Ehrenberg, 2000, p. 142.

[12] Ibidem.

[13] Idem, p.143.

[14] Ibidem.

[15] Ibidem.

[16] Idem, p. 145.

[17] Idem, p. 15.

[18] Idem, p. 177.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Hadler Nortin M., Malades d’inquiétude ?, translated from English by Fernand Turcotte, MD, Québec, PUL, 2010, p. 1.